How Clinicians Test Memory Across Age Groups: Benchmarks, Blind Spots, and Styles of Practice

Written by: neuroaide Team

An empirical look at how clinicians probe learning and retention across development, and what those patterns reveal about everyday practice.

Memory testing isn’t a single task. It’s a chain of decisions: how deeply to probe learning and retention, how broadly to sample formats (lists, stories, designs), and which instruments to rely on. Most clinicians make those decisions intuitively, guided by training, referral patterns, and time constraints.

Unlike overall battery structure, memory assessment is one of the most stylistically variable components of neuropsychological evaluations. Decisions about how many memory tasks to include, which modalities to sample, and how deeply to probe retention versus acquisition are rarely standardized and often shaped by training, habit, and referral context as much as by hypothesis. Looking at memory across age bands offers a particularly clear window into those choices.

When you zoom out across hundreds of evaluations, those individual clinical judgements form recognizable patterns. In this post, we use real-world data from neuroaide to make those patterns visible so you can see where your own habits line up with, or diverge from, what other clinicians are doing.

Methods and Scope

This analysis draws from 588 evaluations completed on neuroaide that included at least one performance-based memory subtest. We defined memory subtests as tasks whose primary interpretive focus is learning and retention (e.g., list learning, story recall, design reproduction).

After applying a guardrail to avoid over-weighting any single high-volume clinician (no one clinician contributes more than 5% of the dataset), the final sample represents a multi-clinician dataset. Cases span five age bands: 0-6, 7-12, 13-17, 18-40, 40+.

Performance tests were decomposed into individual subtests and tagged as primarily verbal or visual based on the dominant input and output format. We then examined memory coverage at two levels: within age bands (population-level sampling) and within the typical evaluation (case-level emphasis).

Finally, a key limitation: these findings reflect the set of memory instruments and subtests that neuroaide currently models in structured form. Instruments that are widely used in the field but not yet represented in neuroaide will not appear here. The goal is not to catalogue every possible memory tool, but to describe how clinicians are using the subset that is visible in this dataset. Together, these decisions allow us to look not only at what memory tools are used, but how memory is functionally sampled across development.

How Much Memory Testing Do Clinicians Actually Do?

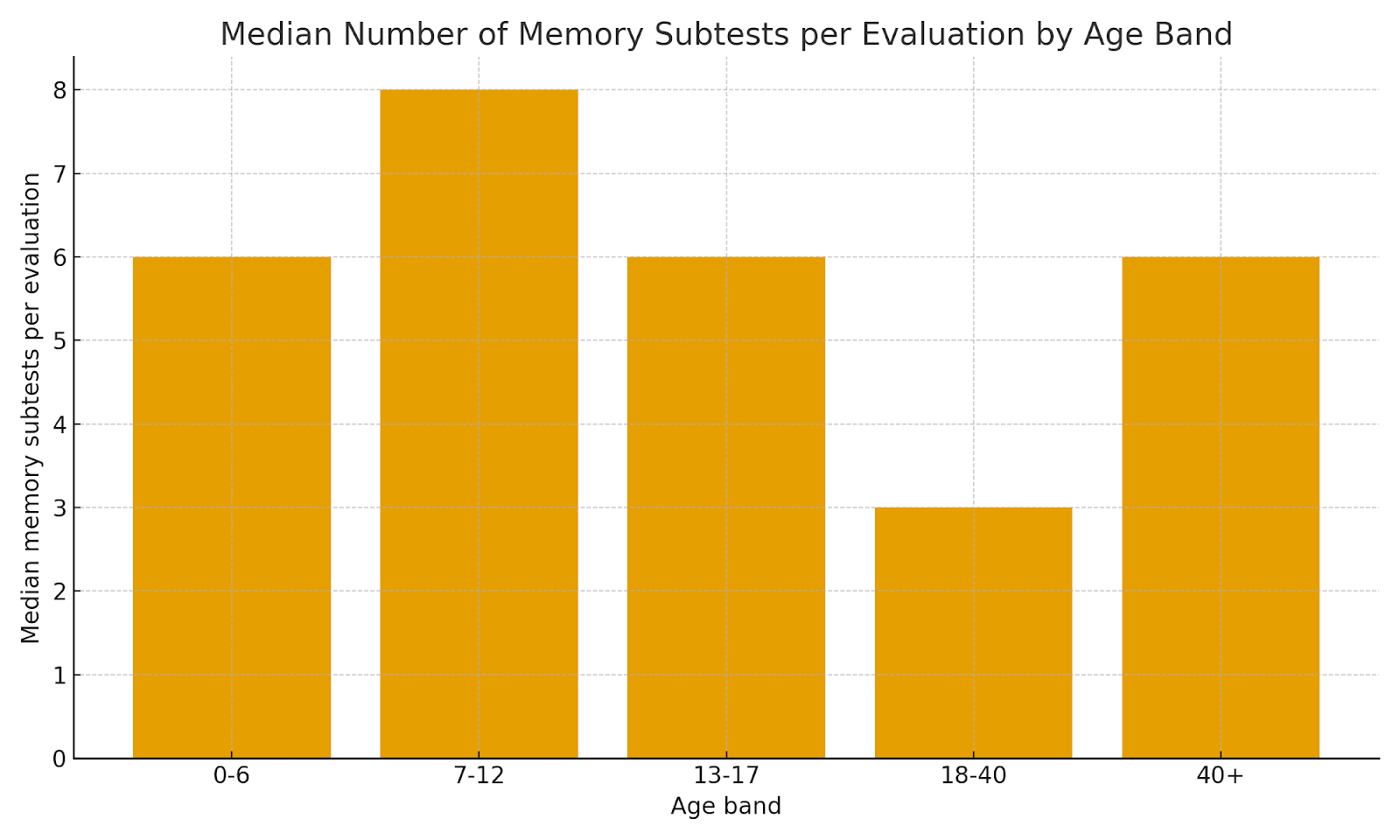

Across clinicians, the typical memory battery is neither a single token task nor a sprawling module. By clinician, the median number of memory subtests per evaluation has a median of 6, with an interquartile range of 3 to 9 subtests. In other words, most clinicians are clustering around 3–9 dedicated memory subtests in a typical case, with a long tail of much leaner and much deeper batteries.

When we break this down by age, school-age evaluations (7–12) sit at the deeper end of that range, with a median of 8 memory subtests. Adolescent (13–17) and younger-child (0–6) evaluations show similarly robust coverage, while adult batteries are somewhat leaner on average. This likely reflects both referral mix (e.g., ADHD/LD workups in pediatrics) and the practical realities of adult assessments (time, fatigue, and competing domains).

A useful way to think about your own practice is in three bands:

• Lean memory coverage: ~1–3 subtests

• Typical memory coverage: ~4–8 subtests

• Extensive memory coverage: 9+ subtests

Most clinicians in this dataset live in the “typical” range, but almost every age band includes both lean and extensive batteries.

What Clinicians Are Actually Sampling: Verbal vs Visual Memory

Looking across all administered memory subtests, about 67% of memory tasks are verbal and 33% are visual. That verbal tilt is present in every age band, but it becomes more pronounced in adolescence and adulthood, where list-learning and story-based tasks are especially common.

Key Insight: When clinicians refer to “memory testing,” they are most often referring to verbal learning and recall. Visual memory is consistently represented, but rarely drives the center of the memory battery—particularly beyond childhood.

At the population level, this means that when clinicians say they are “testing memory,” they are usually testing verbal learning and recall. Visual memory is consistently represented, but it occupies a smaller share of the battery—and that share narrows as clients get older.

When we shift from “all subtests in a band” to “what happens in the average case,” the pattern is even clearer. Within a typical evaluation, verbal memory usually accounts for roughly 70–80% of the memory module, with visual tasks making up the remaining 20–30%. In practical terms, this means that a client whose primary weakness is visual learning may be under-sampled unless the clinician is deliberately building that coverage in.

None of this implies that visual memory should always be 50/50 with verbal—it depends on the referral question. But the default pattern in this dataset is a strong verbal emphasis. If your own practice is heavily verbal, that may be intentional and appropriate; if not, this is a helpful prompt to revisit how often you truly need visual learning and recall to answer the questions being asked.

The Tools Clinicians Use: Anchor Instruments and Supporting Measures

In this dataset, a small set of tools functions as anchor memory instruments, appearing again and again across cases and age bands, while a much longer tail of measures plays a more supporting role.

In this sample, WRAML-3 is the single most common memory instrument, appearing in 286 evaluations. ChAMP, CVLT-3, NEPSY-II, and CVLT-C round out the next four spots. Together, these five tools account for a substantial proportion of all memory modules administered on neuroaide, functioning as de facto anchors in everyday practice.

Beyond those anchors, we see a diverse set of other instruments used more selectively—for particular age bands, referral questions, or training backgrounds. For an individual clinician, this often looks like one or two “home base” instruments, with additional tools brought in when the clinical question or setting demands it.

Within-Instrument Focus: Which Subtests Actually Get Used?

Even within a given instrument, clinicians rarely use every available memory subtest equally. Instead, a small subset tends to carry most of the testing time. To illustrate this, we looked at the subtest profile for the five most commonly used instruments in this dataset.

WRAML-3

ChAMP

NEPSY-II

A consistent pattern emerges across instruments: one or two core subtests show up in nearly every administration of that tool, while additional subtests are used in a narrower subset of cases. That pattern makes sense, clinicians anchor their interpretation on a small number of well-understood tasks, and then add or omit specialized subtests depending on time, referral question, and the client’s profile.

Styles of Memory Practice: Concentrated vs Diverse

To understand how clinicians structure their memory practice, we looked at two things for each clinician: (1) how many different memory instruments they used, and (2) how concentrated their usage was in a small number of tools. The concentration metric (sometimes called a Herfindahl index) is simple in spirit: it is higher when most of a clinician’s cases rely on the same one or two instruments, and lower when their cases are spread more evenly across several tools.

Higher concentration scores indicate greater concentration around a single instrument, with the maximum increasing as more instruments are used; clinicians near the top of the plot rely heavily on one primary instrument, even if they have experience with several.

Key Insight:

Neither concentrated nor diverse memory practice is inherently superior. What matters is whether a clinician’s style reliably produces the data needed to answer their most common referral questions.

Both styles appear in this dataset. Many clinicians spend most of their time with one primary instrument and a small number of supplements; others rotate across several anchors. The key question is not which style is “better,” but whether your style matches your referral mix and documentation needs.

Practical Takeaways: A Quick Self-Audit for Your Memory Batteries

Based on these patterns, a few concrete questions you can ask yourself about your own practice:

- Depth: For the age bands you see most frequently, does your typical memory module fall into the lean (1–3 subtests), typical (4–8), or extensive (9+) range? Is that depth appropriate for the kinds of questions you’re usually trying to answer?

- Balance: Looking at a month of your reports, would you estimate that 70–80% of your memory testing is verbal? Are there cases where you would want a more robust sample of visual learning and recall than you typically collect?

- Instrument mix: What are your anchor memory instruments—the ones you could interpret in your sleep? Which supporting tools do you reach for when the referral question is more complex or atypical?

- Style: Do you recognize yourself more in a concentrated style (a small, stable battery) or a more diverse style (rotating across several instruments)? Is that a deliberate choice, or simply an artifact of training and habit?

These questions can also be useful when reviewing your own reports, not to standardize content, but to assess whether the memory data you collect consistently supports the interpretations you write.

Limitations and How to Read These Trends

These data reflect early adopters of neuroaide and are weighted toward pediatric evaluations. As a result, “overall” memory patterns are heavily influenced by school-age and adolescent cases. Adult and older-adult practice is best interpreted within its own age bands.

Neurodegenerative memory assessment is underrepresented. This evaluation set does not meaningfully include Alzheimer’s-focused or other neurodegenerative memory batteries. Many instruments commonly used in dementia workups are either not modeled in neuroaide today or are rarely used by our current user base, which skews toward pediatric and general adult practice. As a result, the memory patterns described here should not be assumed to reflect typical assessment approaches in specialty memory clinics or geriatric neuropsychology settings.

We did not link referral questions, diagnoses, or setting (school vs. hospital vs. private practice) directly to these analyses. Memory depth and instrument choice can vary dramatically by context, so these findings should be read as global patterns rather than recommendations for specific clinical scenarios.

Finally, we only see the instruments that neuroaide currently models as structured memory measures. If you rely heavily on a tool that doesn’t appear here, that absence reflects product scope, not a lack of use in the field.

This analysis builds on our earlier benchmarking of school-age neuropsychological batteries and reflects neuroaide’s broader goal: making the structure of everyday clinical practice visible without flattening judgment or nuance. Future posts will continue to examine how specific domains are assessed, and how those choices shape both interpretation and reporting.

Subscribe for more neuropsychology trends and insights

Join our mailing list for monthly insights on neuropsychology practice trends, data-driven findings, and how AI is reshaping evaluation and reporting.